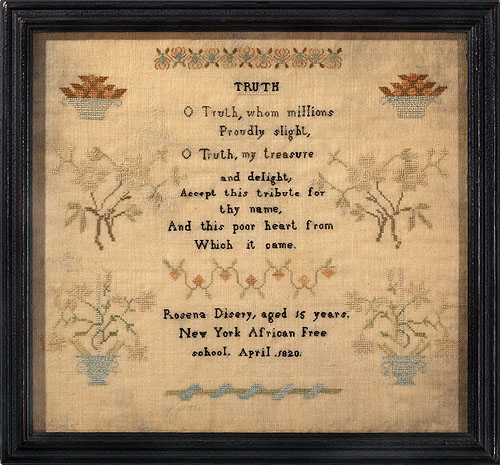

New York African Free School Sampler by Rosena Disery, 1820

In their seminal book, American Samplers (Boston, 1921), Ethel Stanwood Bolton and Eve Johnston Coe of The Massachusetts Society of the Colonial Dames of America, refer to a unique sampler: “Another school in New York had the interesting name of ‘African Free School.’ Rosena Disery made a sampler at this school in 1820. The sampler was seen in a shop, and unfortunately nothing beyond the name of the girl and name of the school were reported” (page 373). It has now been rediscovered, and is only the second known sampler made at the African Free Schools of New York, which existed from 1787 until 1835.

Through extensive research, we have been able to learn much about Rosena Disery, the maker of this sampler, and the life she led. She was the daughter of Nowell and Mary Disery and the wife of Peter Van Dyke, and appears to have lived in New York her entire life. In 1871, when Rosena was approximately 66 years of age and a widow, she deposited funds in Freedman’s Bank. The bank’s records show that she lived at 133 Wooster Street with her son and her sister, and that her occupation was that of “Public Cook.” The archives of Freedman’s Bank are an invaluable resource for researchers of African American families. This institution existed from 1865 to 1874. It was established by a law signed by Abraham Lincoln to create a savings and trust bank to provide greatly needed financial services to former slaves and their dependents, but was available to others. The fact that Rosena attended school in 1820 is a likely indication that she was a free person at that time.

Quite remarkably, we find further information regarding this family in a 1907 publication by Booker T. Washington, The Negro in Business (Hertel, Jenkins & Co). A chapter entitled “The Negro Caterer” informs us that, “One of the professions which was once largely monopolized by members of our race … is that of catering.” Mr. Washington further states that he had come to know of “some very interesting information in regard to the history of the early New York colored caterers which has enabled me to follow the history of the connection of the Negro with the catering business in New York from the days when the city did not extend much above Wall street.” He continues, “Among those who made fortunes were Peter Van Dyke, who owned a place at 133 Wooster street. He became wealthy and left his children and grandchildren in good circumstances.” Although he was deceased by 1871 when Rosena deposited $500 at Freedman’s Bank, Peter Van Dyke was alive in 1860 when a listing in Trow’s New York City Directory, compiled by H. Wilson, included Van Dyke, again at 133 Wooster Street, as a “colored cook.”

The History of the New-York African Free-Schools: From Their Establishment in 1787, to the Present Time; Embracing a Period of More Than Forty Years was written by Charles C. Andrews and printed by Mahlon Day in 1830. In the preface of the book, Mr. Andrews, a teacher at the schools, states: “It has long been desired by the friends of the New-York African Free-Schools, that some account of their rise, progress, and present state, appear before the public, in order, that a more correct idea may be formed, by strangers, of the practicality of imparting the useful branches of education to the descendants of Africans ….” This was done in part in the hopes that others would be encouraged to follow the example of the New York Manumission Society. Many of the gentlemen who had organized the school were Quaker, in keeping with the abolitionist beliefs of their faith. At the time, there was a strong relationship between the Manumission Society, the African Free School and the Quaker community.

Mr. Andrews informs us that a female teacher was hired in 1791 to teach needlework to the girls. After some years in which this branch was discontinued, Miss Lucy Turpen was hired to resurrect the needlework curriculum. Lucy had been educated at the Female Association School, under the auspices of philanthropic Quaker ladies of the city; these schools educated children from families of lesser circumstances. Lucy’s own sampler, worked at the Female Association School No. 3 in 1815, is published as figure 338 in Betty Ring’s Girlhood Embroidery, vol II. The Female Association Schools were acknowledged to be a model for the African Free Schools, and we can now state that their samplers served as models for some of the African Free School samplers as well, in that the composition and motifs of Rosena’s sampler bears strong resemblance to Quaker composition and motifs of the Female Association School samplers. It is very possible that as a young teacher Lucy Turpen taught Rosena Disery in 1820; if not Lucy, Rosena’s teacher was undoubtedly another Female Association School graduate.

The only other known sampler made at any of the African Free Schools is in the collection of the Cooper-Hewitt. Made in 1803 by Mary Emiston, it is also a very interesting sampler, consisting primarily of text, with none of the distinct Quaker characteristics found on Rosena’s sampler.

Rosena Disery’s sampler was purchased by a collector at a shop in Texas sometime between 1930 and 1950; this was likely the location where the sampler was noticed and reported to the authors of American Samplers. Upon her death the collection was bequeathed to her granddaughter who just recently brought the sampler to our attention.

The sampler was worked in silk on wool and is in very good condition, with some slight loss to the wool.

Sampler size: 12” x 13” Frame size: 14” x 15”