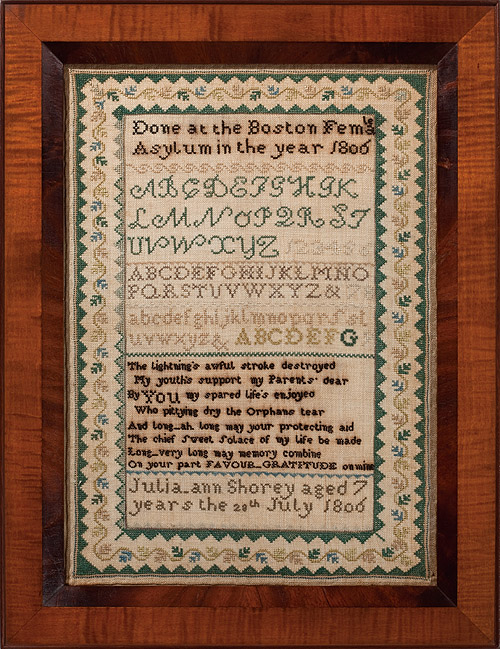

Julia Ann Shorey, Boston Female Asylum, Boston, Massachusetts, 1806

This essay was written for us by Mary Yacovone, Senior Cataloguer, Massachusetts Historical Society. It was Mary’s excellent research into both the institution and the samplermaker that provided much of the fascinating information in this case.

The optimism and earnest display of newly learned skills evidenced on seven-year-old Julia Ann Shorey’s 1806 sampler stitched at the Boston Female Asylum betray little of the curious and tragic story behind it. The first lines of her verse, “The Lightning’s awful stroke destroyed / My youth’s support my Parents’ dear” provides us with a hint, but the rest of the story is even more compelling. Julia was born about 1799, the second child of three born to Miles and Love (Breed) Shorey. Miles was a fourth generation descendant of Samuel Shorey ofYork County,Maine, and Love was a member of the Breed family, a prominent one in the history ofLynn,Massachusetts. Miles was a cordwainer or shoemaker, a member of the working class. He and his young family shared a home onBoston StreetinLynn,Massachusettswith several other people.

One can only assume that the morning of Sunday July 10, 1803was a typical one for the family. Love had recently given birth to a girl, Nabby, and her mother, Abigail Breed, was in Lynnfor a visit from neighboring Salem. When a thunderstorm arose, it may have attracted little notice until the Shorey house was struck, instantly killing Miles and his wife, who at the time was holding the baby in her arms. The History of Lynn records that the “bolt appeared like a ball of fire … struck the western chimney … One branch melted a watch which hung over the chamber mantle, passed over the cradle of a sleeping infant … separated into two branches above the wife and husband …One part struck Mrs. Shorey on the side of her head … the other part entered Mr. Shorey’s bosom …” Newspaper reports, which were widely circulated in the days after the accident, add that Love “had a babe in her arms, which sustained no other injury than having its hair a little burnt.” Although the house was “shattered … considerably,” remarkably none of the seventeen other people reported to be in the house at the time were injured. Miles and Love were buried in a single grave, in the words of Reverend Thomas Cushing Thacher, “Lovely and pleasant in their lives, in their death they were not divided.”

The following Sunday, Rev. Thacher, a Congregational minister inLynn, preached a funeral sermon “occasioned by the death of Mr. Miles Shory and wife, who were instantly killed by lightning.” As one might expect, the main theme of the sermon was the “uncertainty of the time and manner of [death’s] approach—the infinite danger of delaying preparation for our last hour.” Although he makes sure to note that one “may not judge of the characters of persons from their outward circumstances,” he also makes it clear to his hearers that the Shoreys’ tragedy was one of “wonder and amazement. That the same bolt should separate over the heads of two of our fellow creatures … and instantly deprive them of life; that the lives of a large household should be preserved … must convince the most unreflecting of the agency and design of an unerring marksman.” Thacher finishes with prayers for the mourning family, especially the orphan children adding his hope that “in this unfriendly world, may the universal Father take them up. May friends and benefactors be raised up to them, who will cultivate their minds … educate them for God, as well as provide for them in the world.”

So we have three children, suddenly orphans, with few prospects in the world. Reverend William Bentley, a noted diarist and chronicler ofSalemhistory, picks up their story from here. On4 August 1803, he is called upon to baptize Julia and her brother Nehemiah, an event recorded in his own diary, as well as in the vital records ofSalem. He notes in his diary that “the eldest son is to go with Mr. Shorey’s Brother to Berwick & the Daughter in the charge of 3 charitable women inBoston. The youngest at the breast is not yet provided for except by relations.”

In a curious footnote to the story, advertisements regarding the Shorey tragedy begin appearing in theSalemnewspapers in September of 1803 signed by Peter Sanborn, a minister inReading,Massachusetts. In them, Sanborn mentions “many false and groundless reports … to the injury of the character of Mr. Miles Shorey and wife,” that had been spread, using his name to give them “credit and circulation.” Sanborn admits that in a sermon he took notice of the “solemn providence” of the event to warn his parishioners, but that he had “no recollection” of casting aspersions on the Shoreys’ characters. Reverend Bentley helpfully (and somewhat gleefully) supplies the rest of the story in his diary, calling the events a “curious specimen of Pulpit Zeal.” Apparently, Reverend Sanborn, not content to simply make a lesson of the tragedy, “made a particular judgment of it too. He declared the man a Sabbath breaker & that he was at work at his trade on the Sabbath on which he suffered.” Mrs. Abigail Breed, Love’s mother, caught wind of these rumors and rushed to her family’s defense. According to Bentley, she “made it her business to call on Sanborn & she could out talk any man. She finally persuaded him to contradict the fact, that he had said anything implying such charge against Shorey & wife.” Despite Sanborn’s very public—and certainly mortifying--protestations, his parishioners seem to have stuck to their version of the story, at least according to Bentley. Along with Sanborn’s mea culpa, some versions of the advertisement were accompanied by a statement from Shorey’s friends attesting to the “false and groundless” nature of Sanborn’s claims.

With the family broken apart and her siblings dispersed, Julia Ann Shorey, age four, found herself in the care of, in Bentley’s words, those three charitable women of Boston. These turn out to be the extraordinary ladies of the Boston Female Asylum.

The seeds for the Boston Female Asylum were sown in the December 2, 1799issue of J. Russell’s Gazette, Commercial and Political, aBoston newspaper. A correspondent signing herself “A Mother” wrote to express her desire that the ladies of Boston “follow the philanthropic example” of the women of Baltimore who, in the Fall of 1798, had formed the Female Humane Association, an organization of women helping other women. Originally formed to provide direct financial aid to destitute women, by 1800, the women ofBaltimore had amassed sufficient funds to establish a charity school and expand their aid to young girls.

The women of Bostonwere quick to approve “Mother’s” idea; a week later, the Gazette ran a letter signed “A,” pledging to subscribe as much yearly as shall be judged necessary by any number of ladies who shall meet and form themselves into a society, for the purpose of relieving the distresses of females. So it was that in September of 1800, the first meeting of the Boston Female Asylum was held with the aim of establishing a Society to assist “female orphan children from 3 to 10 years of age.” Hannah Stillman, the wife of Boston minister Samuel Stillman was named “first directress” and Susannah Draper became the first governess of the Asylum, charged with the direct care of the girls. Membership at three dollars per year was limited to women, although donations from gentlemen were “gratefully received … and entered with peculiar pleasure on the list of its Benefactors.” By 1801, the annual subscription to the Asylum was some $900 a year, with an additional $620 in donations. Among the earliest subscribers, we find the names of “Mrs. Adams (lady of the President of theU.S.) and Mrs. Adams, lady of His Excellency S. Adams (the Governor of Massachusetts), as well as the names of some three hundred wives and daughters of prominent merchants, ministers, and politicians.”

The Asylum was incorporated by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts on 26 February 1803 and by that year, according to An Account of the Rise, Progress, and Present State, of the Boston Female Asylum, “…already have 31 poor, destitute children been received into it; 6 of whom have been placed in good families, till they shall arrive at the age of 18 years; 25 are now in the Asylum, under the immediate care of Mrs. Ann Baker, the present Governess.” The Account goes on to note that “applications for the admission of Children are frequent, but the Managers can admit no more than their annual Income will enable them to support.”

Although not ideal, life at the Boston Female Asylum seems to have been a good and stable one for the girls in its charge. Among the rules and regulations, we find the requirement that all children attend public worship with their governess every Sunday and in the meantime read the Bible and other religious works. The governess was charged with teaching the girls to “spell, read, and to work in plain Sewing, Knitting and Marking; and those who are old enough, shall mend their own Clothes, and assist … in the domestic business of the family.” At a certain age, girls were “placed out in virtuous families, ‘until the age of eighteen years, or marriage within that age,’ except such, as, from infirmity, may be taught some other business.”

Here, we pick up Julia’s story again. The records of the Boston Female Asylum, held by the Joseph P. Healey Library at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and transcribed by Ann Lainhart, indicate that Julia’s entry into the Asylum was a somewhat controversial one, despite her tragic circumstances. Among the rules of the Asylum’s constitution was that girls from outside of Boston were eligible for admittance only if presented by twenty current subscribers [annual dues-paying members of the Asylum]. Given the extreme circumstances of Julia’s case, apparently some members of the Asylum had “gone rogue” in 1803 and brought Julia into the shelter. At the January 1804 meeting of the Asylum, Mrs. Gray and Mrs. Hay, “the ladies who had for the past half-year benevolently sheltered in the Asylum the child from Lynn,” were notified to “remove her as soon as possible, her stay, being determined a contradiction of the IX article of their Constitution.” At the next monthly meeting, Mrs. Gray argued that Julia’s admission be judged under a different section of the constitution, the one that granted the directors authority and discretion to “take into the Asylum such [other] Female Orphan Children as they may judge suitable objects of their charity.” The matter was not immediately settled in Julia’s favor as the board voted to contact Reverend Thomas Thacher, who had eulogized the Shoreys, to see what care the town of Lynn or others could provide her.

In May, having received no response from Thacher, the ladies of the Asylum were sufficiently moved by Julia’s plight that a unanimous vote to make her a “true and lawful subject” of the Asylum was taken. Sometime later, the Asylum received news that Miles Shorey’s estate was insolvent and that his children were not to receive “one cent out of the estate, and therefore, they must be brought up by charity; or by relations who are not very well able to maintain them.” So Julia (recorded as Juliana in the Asylum’s records) was taken into the Asylum and placed in the family of Henry and Anna Hill. Her life, unfortunately, was not destined to be a long one; by the spring of 1808, Julia was in poor health and had been “removed into the country as the last expedient for recovering her from a dangerous, and uncommon disorder.” She died in August of that year. Echoing the gratitude expressed by Julia on her sampler, in September, her grandmother Abigail Breed wrote a touching note to the directors offering her sincere thanks for the care they had taken of her “dear child” and asking that “the best of Heavens blessings … be granted to each one of you, and your families.”

This is the only known sampler made at the Boston Female Asylum. Interestingly, the quality of the needlework is quite high; the lettering is very carefully formed and indeed the reverse of the sampler is as neatly finished as the front. The teacher employed at the Asylum was obviously very knowledgeable. Worked in silk on linen, the sampler is in excellent condition and it has been conservation mounted into a maple and cherry frame.

Sampler size: 16½” x 12” Frame size: 21½” x 16”

This sampler is from our archives and has been sold.